We recommend sticking with well-known brands when buying accessories, and a recent example illustrates why this is important. Anker, a highly regarded accessory manufacturer, has initiated voluntary recalls of power bank models sold from 2016 to the present due to the risk of overheating, melting, smoke, and fire. Read More from “Anker Recalls Millions of Power Banks: Check Yours Today”

Stay Connected Off the Grid: How to Use Messages via Satellite in iOS 18

If you own an iPhone 14, 15, or 16 and are in the US, Canada, or Mexico, you now have access to a feature that could make all the difference the next time you find yourself staring at the dreaded SOS icon in your status bar. With iOS 18, Apple introduced Messages via satellite, a technology that lets you send and receive text messages even when you’re completely out of range of cellular and Wi-Fi networks. While it’s not a substitute for your usual messaging habits, it’s a powerful tool for minor emergencies, remote travel, or moments when the infrastructure fails you. Read More from “Stay Connected Off the Grid: How to Use Messages via Satellite in iOS 18”

Consider Personal Cyber Insurance

As digital threats become increasingly sophisticated, individuals need protection just as much as businesses do. According to the Federal Trade Commission, Americans lost $12 billion to fraud in 2024, with a significant portion coming from digital scams. While we’d all like to think we’re too savvy to fall for such schemes, even security experts can become victims: Troy Hunt, creator of the Have I Been Pwned site that tracks data breaches, recently fell prey to a sophisticated phishing attack. Read More from “Consider Personal Cyber Insurance”

Make Apple Devices Easier for Family to Access with Secondary Biometrics

It’s only safe to share your iPhone, iPad, and Mac passcodes and passwords with people you trust completely, which typically includes family members whom you would trust with your healthcare and bank accounts. If those people also use your devices regularly, you can simplify their access by adding their fingerprint to Touch ID or their face to Face ID. Touch ID allows you to add up to five fingerprints, while Face ID provides an option for a second face. Both can be easily set up in Settings > Face/Touch ID & Passcode (iPhone and iPad) and System Settings > Touch ID & Password (Mac). Read More from “Make Apple Devices Easier for Family to Access with Secondary Biometrics”

Did You Know You Can Rename Many Bluetooth Devices?

All Bluetooth devices come with a name, but those names are often difficult to decipher, such as ATUMTEK, DX01Gu, and MY-CAR, making it hard to remember which is which in your iPhone’s Bluetooth settings. What you may not realize is that you can rename many Bluetooth devices to tidy up that list. Go to Settings > Bluetooth, connect to the device, and tap the blue ⓘ button to the right of its name. Read More from “Did You Know You Can Rename Many Bluetooth Devices?”

Switch Between Apps Fluidly on Face ID iPhones

The ongoing threat of tariffs raising the price of iPhones has recently prompted some people to upgrade from an old Touch ID iPhone to a new iPhone 16. Although most have adjusted well to Face ID, few are aware of the app-switching shortcut exclusive to Face ID iPhones. To access the App Switcher on a Face ID iPhone, you must swipe up slightly from the bottom of the screen and then continue the swipe to the right. However, Face ID experts rarely do that. Instead, they just swipe right and left on the bar at the bottom of the screen to switch between apps—it’s much faster and easier, albeit hard to discover. Read More from “Switch Between Apps Fluidly on Face ID iPhones”

Ten Tips for Making the Best Use of AI Chatbots

Since ChatGPT launched in late 2022, people have been using AI chatbots to brainstorm, speed up research, draft content, summarize lengthy documents, analyze data, assist with writing and debugging code, and translate text into other languages. Recently, the major chatbots have gained Web search capabilities, allowing them to access live information beyond their training model data. Read More from “Ten Tips for Making the Best Use of AI Chatbots”

At WWDC 2025, Apple Unveils Liquid Glass and Previews New OS Features

Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference keynote was a lightning-fast 92-minute tour of Apple’s vision for how we’ll use its products in the next year. Apple wove two themes through the presentation: the new Liquid Glass design language will provide a consistent look and feel across all its platforms, and Apple Intelligence-powered features will continue to appear throughout the ecosystem. The other overarching news is that Apple is adopting a new annual versioning approach, similar to car model years, so the version number for each operating system will be 26. Read More from “At WWDC 2025, Apple Unveils Liquid Glass and Previews New OS Features”

Choosing the Best Mac for a College-Bound Student in 2025

Is your child heading off to college soon? Now is a good time to consider getting them a new Mac, especially if their current computer is old or unreliable, is shared with other family members, or was a school loaner. If you haven’t been keeping up with Apple’s Mac lineup, you might be unsure which model is the best choice. Read More from “Choosing the Best Mac for a College-Bound Student in 2025”

Clean Your iPhone’s Camera Lens

Serious photographers take care of their lenses. The rest of us just stuff our iPhones into our pockets or purses and pay no attention to the fingerprints and grime they collect. If your iPhone’s camera lens is smudged, it will impact the quality of your photos. Take a few seconds to polish it with a microfiber cloth now and then, or, you know, simply wipe it with the edge of your T-shirt. Your photos will thank you. Read More from “Clean Your iPhone’s Camera Lens”

Beware Domain Name Renewal Phishing Attacks

Most phishing attacks are easy to identify, but we’ve just seen one that’s more likely to evade detection. Those who own personal or business Internet domain names—to personalize their email or provide an online presence for their website—may receive fake messages claiming that a domain has been deactivated due to a payment issue. Because scammers can determine when domain names are due to expire and the name of the company hosting the domain, the urgency triggered by a message that appears to be from the domain host and arriving near the renewal date may cause someone to click a link they shouldn’t. This particular one wasn’t even that well crafted and still caused the recipient brief concern until they manually went to DreamHost and verified that nothing was wrong with their domain payment. Stay alert out there! Read More from “Beware Domain Name Renewal Phishing Attacks”

Try Blip for Fast Transfers of Any Size Between Platforms

For file transfers, Apple users routinely rely on tools like AirDrop, Messages, email, cloud services, and public sharing websites, but these solutions can fall short when dealing with very large files, sharing across platforms, or confidential data. For such scenarios, Blip offers a reliable solution that works across Macs, iPhones, iPads, Android devices, Windows, and Linux machines. It transfers files of any size directly between devices, with no intermediate servers, encrypting its traffic for security. It handles uncompressed folders, offers high transfer speeds, and automatically resumes interrupted transfers—particularly valuable features when working with large media files or project folders. Blip is free for personal use or $25 per month for commercial use, making it easy to determine if it will be helpful for your business. Read More from “Try Blip for Fast Transfers of Any Size Between Platforms”

Apple Silicon Macs Can’t Boot from the DFU Port

Booting from an external SSD (hard disks are too slow) provides a convenient way to test specific versions of macOS or troubleshoot problems with your Mac’s internal storage. However, a little-known gotcha has caused untold hair loss among those trying to boot from an external drive. Macs with Apple silicon cannot start up from external drives connected to their DFU (device firmware update) USB-C port. The only way to determine which port this is on a given Mac is to look it up on Apple’s website. If your Mac won’t boot from an external drive, connect it to a different USB-C port. Read More from “Apple Silicon Macs Can’t Boot from the DFU Port”

Make Sure to Check Settings on Multiple Devices

We recently helped someone having trouble with 1Password requesting their password repeatedly on their iPad, but not on their iPhone. Since 1Password’s data syncs between devices, this person didn’t realize they needed to configure the app’s security settings separately for each device. It’s appropriate for 1Password to separate security settings—one device could be used in a much more sensitive environment than another—but it’s also easy to see how a user might be confused about the difference in behavior. All this is to say that if you are annoyed by an app or operating system behaving differently depending on the device you’re using, compare the settings and ensure they’re set appropriately for each device. Read More from “Make Sure to Check Settings on Multiple Devices”

Consider Business Cyber Insurance

When discussing digital security, we typically focus on preventive measures, such as using strong passwords with a password manager, enabling multi-factor authentication, keeping systems up to date, maintaining regular backups, and training employees to recognize potential security threats. While these practices are essential, they don’t guarantee complete protection. Read More from “Consider Business Cyber Insurance”

Use AirPlay to Mirror or Extend Your Mac’s Display

Apple’s AirPlay is one of those low-level technologies that’s more capable than many people realize. In addition to allowing you to stream video and audio from an iPhone, iPad, or Mac to an Apple TV connected to a large-screen TV, AirPlay also enables you to use that TV as an external Mac display, either mirroring what’s on your Mac’s screen or extending the desktop. It even allows you to turn one Mac into a display for another. Read More from “Use AirPlay to Mirror or Extend Your Mac’s Display”

Why Every Business Needs an AI Policy

Are employees at your company surreptitiously using artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, and Gemini for everyday business tasks? It’s likely. An October 2024 Software AG study found that half of all employees use “shadow AI” tools to enhance their productivity, and most would continue using them even if explicitly banned by their employer. Read More from “Why Every Business Needs an AI Policy”

Why Passkeys Are Better than Passwords (And How to Use Them)

No one likes passwords. Users find managing them annoying, and website managers worry about login credentials being stolen in a data breach. The industry has developed a better solution: passkeys. Read More from “Why Passkeys Are Better than Passwords (And How to Use Them)”

With iOS 18.2 and Later, You Can Share the Location of Lost Items in Find My

In iOS 18.2, Apple enhanced the Find My app, enabling you to create a temporary Web page that shares the location of a lost AirTag or other Find My-tracked item. You don’t need to know the person’s email address or share any other information, and the link automatically expires after a week. It’s a great way to enlist others in the search for a lost item, but the big win is sharing with an airline to help them track the location of misdirected luggage. Read More from “With iOS 18.2 and Later, You Can Share the Location of Lost Items in Find My”

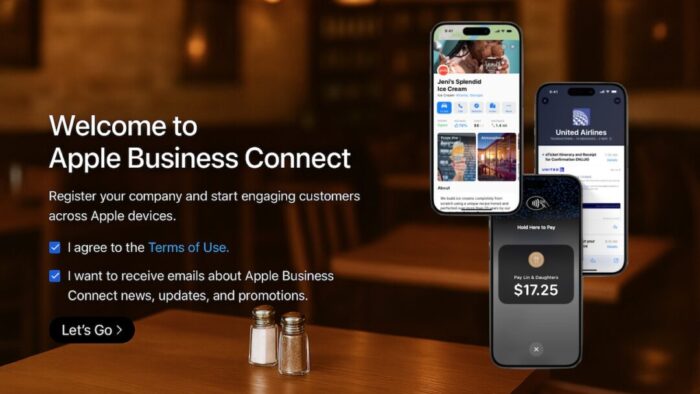

Run a Business? Sign Up with Apple Business Connect

Every company today conducts business online, by sending email, if nothing else. That’s true even if your firm operates primarily in the physical world—customers undoubtedly find you by browsing in Apple Maps, searching in Spotlight, and asking Siri for directions. If you sell products, you probably take Apple Pay.

Apple Business Connect is a free program designed to help businesses enhance their brands everywhere they appear on Apple devices, including Maps, Wallet, Siri, Calendar, Messages, Spotlight searches, and more. Read More from “Run a Business? Sign Up with Apple Business Connect”